Somewhere between the exotic and the kitsch is real Delhi. —Ranjana Sengupta

Delhi (deservedly) has a reputation as a macho, aggressive, sleazy city—for gang rapes, institutional misogyny, and paranoid women packing pistols—and its power elites are still dense with Stalinesque moustaches. But it has another side, too. Whisper it (a touch breathily, with a coy pout and a flirtatious twirl of your cheerleading cane): D-Town is camp.

Professional sociopath A.A. Gill wrote recently, ‘If New York is a wise guy, Paris a coquette, Rome a gigolo and Berlin a wicked uncle, then London is an old lady who mutters and has the second sight. She is slightly deaf, and doesn’t suffer fools gladly.’ Delhi, then, might be an ageing tsarina: ruthless, capricious, avaricious, oversexed, paranoid—and fond of bright colours, pretty trinkets, and cross-dressing. Like all grandes dames, she’s showy, hard to love, easy to photograph.

Camp, in Susan Sontag’s famous formulation, is a sensibility that revels in artifice, stylization, irony, playfulness, theatricality, and exaggeration rather than content. It ‘sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a “lamp”; not a woman, but a “woman”‘. With a knowing wink, it embraces the garish, the kitsch, the sentimental. It’s good because it’s awful.

Camp, in Susan Sontag’s famous formulation, is a sensibility that revels in artifice, stylization, irony, playfulness, theatricality, and exaggeration rather than content. It ‘sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a “lamp”; not a woman, but a “woman”‘. With a knowing wink, it embraces the garish, the kitsch, the sentimental. It’s good because it’s awful.

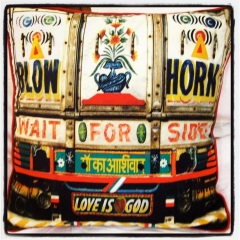

Everywhere you turn in Delhi, you glimpse camp’s potential, sitting prettily atop the muscular highways and throbbing noise. It’s there in the sashaying yellow hips of autorickshaws in traffic, the painted trucks with their big warbling horns, the sultry-eyed, improbably skinny young Roadside Romeos slinking snake-hipped down the streets in their shiny purple shirts. It’s there in the childishly sweet vivid orange whirl of jalebis, the love of Bollywood song and dance, the pot-bellied jollity of Buddha and Ganesh, the tendency for melodrama in politics and relationships alike. It’s even sometimes there in the faint undercurrent of slightly self-conscious menace on some streets or some evenings—like staring at Steve Buscemi’s upper lip fur.

Imperial rule  of course had more than its fair share of high camp, as the foppish Britishers Carried On Up The Khyber with their cocktails, uniforms, and strange obsessions with deviant sexuality (see Anne McClintock’s brilliantly titled Imperial Leather). Colonial-era ‘tropical gothic’ architecture is archetypal camp: the flamboyance, the kitschy imagery, the fakery (wealthy Brits like Thomas Metcalfe would even build faux-mediaeval monuments to spice up their views). Edwin Lutyens himself—a friend of Vita Sackville-West—was an ostentatious mixture of ‘joker and buffoon’. In his extravagantly orchestrated New Delhi, neoclassical lines flirt with odd domes, cupolas, and elephant motifs, in two shades of pink Agra sandstone. Butch, non?

of course had more than its fair share of high camp, as the foppish Britishers Carried On Up The Khyber with their cocktails, uniforms, and strange obsessions with deviant sexuality (see Anne McClintock’s brilliantly titled Imperial Leather). Colonial-era ‘tropical gothic’ architecture is archetypal camp: the flamboyance, the kitschy imagery, the fakery (wealthy Brits like Thomas Metcalfe would even build faux-mediaeval monuments to spice up their views). Edwin Lutyens himself—a friend of Vita Sackville-West—was an ostentatious mixture of ‘joker and buffoon’. In his extravagantly orchestrated New Delhi, neoclassical lines flirt with odd domes, cupolas, and elephant motifs, in two shades of pink Agra sandstone. Butch, non?

Sontag pinpointed two kinds of camp: naive Pure Camp, and Camp Which Knows Itself To Be Camp. In the hands of Delhi’s middle classes, Delhi’s unconsciously limp wrist becomes a deliberate sardonic eyebrow raise and a Hellooo Sailor! flourish. Shah Rukh Khan pirouettes in drag for Indian film awards. The swanky markets are full of boutiques selling unashamedly garish (and pricey) consumer goods covered in Quintessentially Indian Symbols: rickshaw cushions and hijra makeup bags and ashtrays with cartoon turbaned Sikhs—and, in the new May Day Cafe, even cappuccino cups with the hammer and sickle emblazoned on them in an (unwittingly?) hilarious pastiche of coffee-house revolution. In the malls, my fellow South Delhiites eat Haldiram’s sanitised ‘street food’ in a floodlit refrigerated dystopian hell soundtracked by Lady Gaga. For both of us, braving the dirt of sprawling Old Delhi is a touristy adventure—dare we gobble a real kebab? (Answer: yes, because Delhi belly is ironic and self-referential.) Even international development becomes camp, trying to take itself seriously even while it blasts out ‘Sexy Bitch’ over impeccable lawns and expats wryly sipping vodka nimbu pani.

Sontag pinpointed two kinds of camp: naive Pure Camp, and Camp Which Knows Itself To Be Camp. In the hands of Delhi’s middle classes, Delhi’s unconsciously limp wrist becomes a deliberate sardonic eyebrow raise and a Hellooo Sailor! flourish. Shah Rukh Khan pirouettes in drag for Indian film awards. The swanky markets are full of boutiques selling unashamedly garish (and pricey) consumer goods covered in Quintessentially Indian Symbols: rickshaw cushions and hijra makeup bags and ashtrays with cartoon turbaned Sikhs—and, in the new May Day Cafe, even cappuccino cups with the hammer and sickle emblazoned on them in an (unwittingly?) hilarious pastiche of coffee-house revolution. In the malls, my fellow South Delhiites eat Haldiram’s sanitised ‘street food’ in a floodlit refrigerated dystopian hell soundtracked by Lady Gaga. For both of us, braving the dirt of sprawling Old Delhi is a touristy adventure—dare we gobble a real kebab? (Answer: yes, because Delhi belly is ironic and self-referential.) Even international development becomes camp, trying to take itself seriously even while it blasts out ‘Sexy Bitch’ over impeccable lawns and expats wryly sipping vodka nimbu pani.

The dark side of camp, as Sontag noted, is that it forever converts the serious to the frivolous. It is permanently ‘disengaged, depoliticized—or at least apolitical’, trivialising the unpalatable. It ‘proposes a comic vision of the world. But not a bitter or polemical comedy. If tragedy is an experience of hyperinvolvement, comedy is an experience of underinvolvement, of detachment’. India’s real problems are only admitted in their most photogenic and sentimental guises, and difficult questions vanish in a puff of Old Spice.

The dark side of camp, as Sontag noted, is that it forever converts the serious to the frivolous. It is permanently ‘disengaged, depoliticized—or at least apolitical’, trivialising the unpalatable. It ‘proposes a comic vision of the world. But not a bitter or polemical comedy. If tragedy is an experience of hyperinvolvement, comedy is an experience of underinvolvement, of detachment’. India’s real problems are only admitted in their most photogenic and sentimental guises, and difficult questions vanish in a puff of Old Spice.

For Marxist cultural theorists, kitsch is a great threat: it is a type of false consciousness, deliberately encouraging a passive, consumerist response that distracts people from their very real social alienation. As Milan Kundera argued, it equals ‘the absolute denial of shit’. Camp sugarcoats reality, Photoshops it, places a pair of heart-shaped rose-tinted Lolita spectacles on it. We must peer through its consumerist veil to the Truth beneath.

But in tipsier moments, I can’t help but suspect there is no dividing line between kitsch and reality in this strange academic life—not in Delhi, not in tweed-encrusted snuff-snorting Oxford, not in the prettily Sisyphean development world—and certainly not in this blog. So I’ll continue hoovering up Horn Please placemats and slightly sinister faceless sari mugs, and hoard them right next to my saintly Bulgarian icon and Russian dolls. And next time I’m having a nihilistic thought, I’ll stroke them and solemnly say to myself, ‘Don’t be so absurd!’